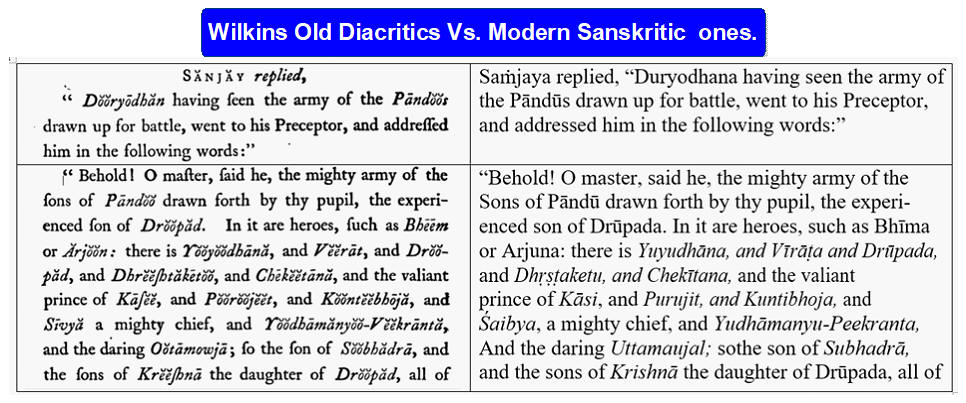

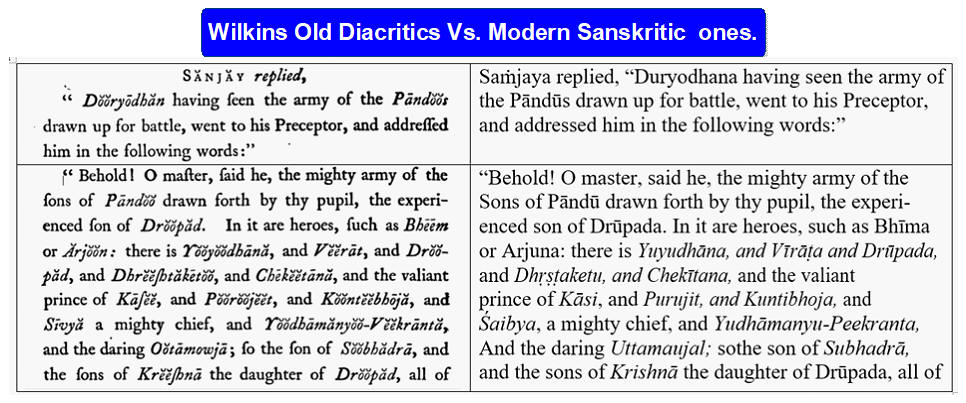

Wilkins published in 1785 the very first edition in English. He learnt Sanskrit in Calcutta from his teacher Pundit Kasinatha.

The Bhagavad-Gītā

Or

Dialogues of Krishna and Arjuna

The Eighteen Lectures

With Notes

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL

IN THE ANCIENT LANGUAGE OF THE BRAHMAN

By CHARLES WILKINS

1785

L E C T U R E. I.

BhagavadGita-Wilkinson.jpg

BhagavadGita-Wilkinson.jpg

SENIOR MERCHANT IN THE SERV(CE OF THE. HONOURABLE THE EAST INDIA COMPANY., ON

THEIR BENGAL ESTABLISHMENT

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR C. NOURSE.,

OPPOSITE CATHERINE-STREET, IN THE STRAND

M.DCC.LXXXV.

MAT 3Oth, 1785.

THE following Work is published under the authority of the Court of Directors of

the East India Company, by the particular desire and recommendation of the

Governor General of India; whose letter to the Chairman of the Company will

sufficiently explain the motives for its publication, and furnish

the best testimony of the fidelity, accuracy, and merit of the Translator.

The antiquity of the original, and the veneration in which it hath been held for

so many ages, by a very considerable portion of the human race, must render it

one of the greatest curiosities ever presented to the literary world.

TO

NATHANIEL SMITH, ESQUIRE.

SIR.

To you, as to the first member of the first commercial body, not only of the

present age, but of all the known generations of mankind, I presume to offer,

and to recommend through you, for an offering to the public, a very curious

specimen of the Literature, the Mythology, and Morality of the ancient Hindūs.

It is an episodical extract from the " Mahabharat," a most voluminous poem,

affirmed to have been written upwards of four thousand years ago, by Krishna

Dwypayana Vyasa, a learned Brahmin; to whom is also attributed the compilation

of “The Four " Vedas (Bēdes), the only existing original scriptures of the

religion of Brahma; and the composition of all the Puranas, which are to this

day taught in their schools, and venerated as poems of divine inspiration. Among

these, and of superior estimation to the rest, is ranked the Mahabharat. But if

the several books here enumerated be really the productions of their reputed

author, which is greatly to be doubted, many argument & may be adduced to

ascribe to the fame source the invention of the religion

itself, as well as its promulgation: and he must, at all events.,.

claim-

[ 6 ]

aim the merit of having first reduced the gross and scattered tenet&

of their former faith into a scientific and allegorical system.

The Mahabharat contains the genealogy and general history of the house of

Bharata, so called from Bharata its founder; the epithet Maha, or Great, being

prefixed in token of distinction: but its more particular object is to relate

the dissentions and wars of the two great collateral branches of it, called

Kurus and Pandavas; both lineally descended in the second degree from

Vichitravirya, their common ancestor, by their respective fathers Dhṛitarāshṭra

and Pandu.

The Kurus, which indeed is sometimes used as a term comprehending the whole

family, but most frequently applied as the patronymic of the elder branch alone,

are said to have been one hundred in number, of whom Duryodhana was esteemed the

head and representative even during the life of his father,. who was

incapacitated by blindness. The sons of Pandu were five; Yudhishthira, Bhima,

Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva who, through the artifices of Duryodhana, were

banished, by their uncle and guardian Dhṛitarāshṭra, from Hastinapura, at that

time the seat of government of Hindustan.

The exiles, after a series of adventures, worked up with a won derful fertility

of genius and pomp of language into a thousand sublime descriptions, returned

with a powerful army to avenge their wrongs, and assert their pretensions to the

empire in right of their father; by whom, though the younger brother, it had

been held while he lived, on account of the disqualification already mentioned

of Dhṛitarāshṭra.

In this fiat the episode opens, and is called "The Gītā of "Bhagvat," which is

one of the names of Kṛṣṇa. Arjuna. Is represented as the favorite and pupil of

Kṛṣṇa, here taken for God himself, in his last Avatar, or descent to earth in a

mortal form.

[ 7 ]

The Preface of the Translator will render any further explana- tion of the Work

unnecessary. Yet something it may be allowable for me to add respecting my own

judgment of a Work, which I have thus informally obtruded on your attention, as

it is the only ground on which I can defend the liberty which I have taken.

Might I, an unlettered man, venture to prescribe bounds to the latitude of

criticism, I should exclude, in estimating the merit of such a production, all

rules drawn from the ancient or modern literature of Europe, all references to

such sentiments or manners as are become the standards of propriety for opinion

and action i11 our own modes of life, and equally all appeals to our revealed

tenets of religion, and moral duty. I should exclude them, as by no means

applicable to the language. sentiments, manners, or morality appertaining to a

system of society with which we have been for ages unconnected, and of an

antiquity preceding even the first efforts of civilization in our own quarter of

the globe, which inspect to the general diffusion and common participation of

arts and sciences, may be now considered as one community.

I would exact from every reader the allowance of obscurity, absurdity, barbarous

habits, and a perverted morality. Where the reverse appears, I would have him

receive it (to use a familiar phrase) as so much clear gain, and allow it a

merit proportioned to the disappointment of a different expectation.

In effect, without bespeaking this kind of indulgence, I could hardly venture to

persist in my recommendation of this production for public notice.

Many passages will be found obscure, many will seem redundant ; others will be

found clothed with ornaments of fancy unsuited to our taste, and some elevated

to a track of sublimity into. which our habits of judgment will find it

difficult to pursue them; but few which will shock either our religious faith or

moral sentiments. Something too must be allowed to the subject itself, which

[ 8 ]

is highly metaphysical, to the extreme difficulty of rendering abstract terms by

others exactly corresponding with them in another language, to the arbitrary

combination of ideas, in words expressing unsubstantial qualities, and more, to

the errors of interpretation. The modesty of the Translator would induce him to

defend the credit of his work, by laying all its apparent defects to his own

charge, under the article last enumerated; but neither does his accuracy merit,

nor the work itself require that concession.

It is also to be observed, in illustration of what I have premised, that the

Brahmans are enjoined to perform a kind of spiritual discipline, not, I believe,

unknown to some of the religious orders of Christians in the Roman Church. This

consists in devoting a certain period of time to the contemplation of the Deity,

his at.. tributes, and the moral duties of this life. It is required of those

who practice this exercise, not only that they divest their minds of all sensual

desire, but that their attention be abstracted from every external object, and

absorbed, with every sense, in the prescribed subject of their meditation. I

myself was once a witness of a man employed in this species of devotion, at the

principal temple of Banaras. His right hand and arm were enclosed in a loose

sleeve or bag of red cloth, within which he passed the beads of his rosary, one

after another, through his fingers, repeating with the touch of each (as I was

informed) one of the names of God, while his mind labored to catch and dwell on

the idea of the quality which appertained to it, and hewed the violence of its

exertion to attain this purpose_ by the convulsive movements of all his

features, his eyes being at the same time closed, doubtless to affect the

abstraction. The importance of this duty cannot be better illustrated, nor

stronger marked, than by the last sentence· with which Krishna closes his

instruction to Arjuna, and which is properly the conclusion of the Gītā: _"Hath

what I have been. " speaking. O Arjuna, been heard with the mind fixed to one

point .

[ 9. ] .

" Is the distraction of thought, which arose from thy ignorance, removed?"

To those who have never been accustomed to this separation of the mind from the

notices of the senses, it may not be easy to conceive by what means such a power

is to be attained; since even the most studious men of our hemisphere will find

it difficult to restrain their attention but that it will wander to some object

of present sense or recollection; and even the buzzing of a fly will sometimes

have the power to disturb it. But if we are told that there have been men who

were successively, for ages past, in the daily habit of abstracted

contemplation, begun in the earliest period. of youth, and continued in many to

the maturity of age, each adding some portion of knowledge to the store

accumulated by his predecessors; it is not assuming too much to conclude, that,

as the mind ever gathers strength, like the body, by exercise, so in such an

exercise it may in each have acquired the faculty to which they aspired, and

that their collective studies may have led them to the discovery of new tracks

and combinations of sentiment, totally different from the doctrines with which

the learned of other nations are acquainted: doctrines, which however

speculative and subtle, stil1, as they possess the advantage of being derived

from a source so free from every adventitious mixture, may be equally founded in

truth with the most simple of our own. But as they must differ, yet more than

the most abstruse of ours, from the common modes of thinking, so they will

require consonant modes of expression, which it may be impossible to render by

any of the known terms of science in our language, or even to make them

intelligible by definition. This is probably the cafe with some of the Englsh

phrases, as those of "Action," "Application,'' " Practice," &c. which occur in

Mr. Wilkins's translation; and others, for the reasons which I have recited, he

has left with the same sounds in which he found them.. When the text is rendered

obscure from such causes, candor requires

[ IO ]

that credit be given to it for some accurate meaning, though we may not be able

to discover it ; and that we ascribe their obscurity to the incompetency of our

own perceptions, on so novel an application of them, rather than to the less

probable want of perspicuity in the original composition.

With the deductions, or rather qualifications, which I have thus premised, I

hesitate not to pronounce the Gītā a performance of great originality; of a

sublimity of conception, reasoning, and diction, almost unequalled; and a single

exception, among all the known religions of mankind, of a theology accurately

corresponding with that of the Christian dispensation., and most powerfully

illustrating its fundamental doctrines.

It will not be fair to try its relative worth by a comparison with the original

text of the first standards of European composition; but let these be taken even

in the most esteemed of their prose translations; and in that equal scale let

their merits be weighed. I should not fear to place, in opposition to the best

French versions of the most admired passages of the Iliad or Odyssey, or of the

1st and 6th Books of our own Milton, highly as I venerate the latter, the

English translation of the Mahabharat.

One blemish will be found in it, which will scarcely fail to make its own

impression on every correct mind.; and which for that reason I anticipate. I

mean, the attempt to describe spiritual ·existences by terms and images which

appertain to corporeal forms. Yet even. in this respect it will appear lefs

faulty than other works with which I have placed it in competition; and,

defective as it may at first appear, I know not whether a doctrine so elevated

above common perception did not require to be introduced by such ideas as were

familiar to the mind, to lead it by a gradual advance to the pure and abstract

comprehension of the subject: This will seem to have been, whether intentionally

or accidentally., the order which is followed by the author of the Gītā;

and so far at least he soars

[ 11 ]

far beyond all competitors in this species of composition. Even the frequent

recurrence of the same sentiment, in a variety of dress, may have been owing to

the same consideration of the extreme intricacy of the subject, and the

consequent necessity of trying different kinds of exemplification and argument,

to impress it with due conviction on the understanding. Yet I believe it will

appear, to an attentive reader, neither deficient in method, nor in perspicuity.

On the contrary, I thought it at the first reading, and more so at the second,

clear beyond what I could have reasonably expected, in a discussion of points so

far removed beyond the reach of the senses, and explained through so foreign a

medium.

It now remains to say something of the Translator, Mr. Charles Wilkins. This

Gentleman two whose ingenuity, unaided by models for imitation, and by artists

for his direction, your government is indebted for its printing-office, and for

many official purposes to which it has been profitably applied, with an extent

unknown in Europe, has united to an early and successful attainment of the

Persian and Bengal languages, the study of the Sanskrit. To this he dev-oted

himself with a perseverance of which there are few examples, and with a success

which encouraged him to _under take the translation of the Mahabharat. This book

is said to consists _of more than one hundred thousand metrical stanzas, of

which he has at this time translated more than a third; and, if I may trust to

the imperfect tests by which I myself have tried a very small portion of it,

through the medium of another language; he has rendered it with great accuracy

and fidelity. Of its elegance, and the skill with which he has familiarized (if

I may so express it) his own native language to so foreign an original, I may

not speak, as from the specimen herewith presented, whoever reads it will judge

for himself

[ 12 ]

Mr. Wilkins's health having suffered a decline from the fatigues of business,

from which his gratuitous labors allowed him no relaxation, he was advised to

try a change of air for his recovery. I myself recommended that of Banaras, for

the fake of the additional advantage which he might derive from a residence in a

place which is considered as the first seminary of Hindu learning; and I

promoted his application to the Board, for their permission to repair thither,

without forfeiting his official appointments during the term of his absence.

I have always regarded the encouragement of every species of life useful

diligence, in the servants of the Company, as a duty appertaining to my office;

and have severely regretted that I have possessed such scanty means of

exercising it, especially to such as required an exemption from official

attendance; there being few emoluments in this service but such as are annexed

to official employment., and few offices without employment. Yet I believe I may

take it upon me to pronounce, that the service has at no period more abounded

with men of cultivated talents, of capacity for business, and liberal knowledge;

qualities which reflect the greater luster on their possessors, by having been

the fruit of long and labored application, at a season of life, and with a

license of conduct, more apt to produce dissipation than excite the desire of

improvement.

Such studies, independently of their utility, tend, especially when the pursuit

of them is general, to disuse a generosity of sentiment:, and a disdain of the

meaner occupations of such minds as are left nearer to the state of uncultivated

nature; and you, Sir, will believe me, when I assure you, that it is on the

virtue, not the ability of their servants, that the Company must rely for the

permanency of their dominion.

Nor is the cultivation of language and science, for such are the studies to

which I allude., useful only in forming the moral character and habits of the

service.

[ 13 ]

Every accumulation of knowledge,. and especially such as is obtained by social

communication with people over whom we exercise a dominion founded on the right

of conquest, is useful to the state : it is the gain of humanity: in the

specific instance which I have stated, it attracts and conciliates distant

affections; it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in

subjection; and it imprints on the hearts of our own countrymen the sense and

obligation of benevolence. Even in England, this effect of it is greatly

wanting. It is not very long since the inhabitants of India were considered by

many, as creatures scarce elevated above the degree of savage life; nor, I fear,

is that prejudice yet wholly eradicated, though surely abated. Every instance

which brings their real character home to observation will impress us with a

more generous sense of feeling for their natural rights, and teach us to

estimate them by the measure of our own. But such instances can only be obtained

in their writings and these will survive when the British dominion in India will

have long ceased to exist, and when the sources which it once yielded of wealth

and power are left to remembrance.

If you, Sir, on the perusal of Mr. Wilkins's performance, shall judge it worthy

of so honorable a patronage, may I take the further liberty to request that you

will be pleased to present it to the Court of Directors, for publication by

their authority, and to use your interest to obtain it its public reception will

be the test of its real merit, and determine Mr. Wilkins in the prosecution or

cessation of his present laborious studies. It may, in the first event, clear

the way to a wide and unexplored field of fruitful knowledge; and suggest, to

the generosity of his honorable employers,. a desire to encourage the first

persevering ad venturer in a service in which his example will have few

followers, and most probably none, if it is to be performed with the gratuitous

labor of years left to the provision of future subsistence:

the:

[ 14 ]

: for the study of the Sanskrit cannot, like the Persian language, be applied to

official profit, and improved with the official exercise of it. It can only

derive its reward, beyond the breath of fame, in a fixed endowment. Such bas

been the fate of his predecessor, Mr. Halhed, whose labors and incomparable

genius, in two useful productions, have been crowned with every success that the

public estimation could give them; nor will it detract from the no less original

merit of Mr. Wilkins, that I ascribe to another the title of having led the way,

when I add that this example held out to him no incitement to emulate it, but

the prospect of barren applause. To say more, would be disrespect; and I believe

that I address myself to a gentleman who possesses talents congenial with those

which I am so anxious to encourage, and a mind too liberal to confine its

beneficence to such arts alone as contribute to the immediate and substantial

advantages of the state.

I think it proper to assure you, that the subject of this address, and its

design, were equally unknown to the person who is the object of it; from whom I

originally obtained the translation for another purpose, which on a second

revisal of the work I changed, from a belief that it merited a better

destination.

A mind rendered susceptible by the daily experience of unmerited reproach, may

be excused if it anticipates even unreasonable or improbable objections. This

must be my plea for any apparent futility in the following

observation. I have seen an extract from a foreign work of great literary

credit, in which my name is mentioned, with very undeserved applause, for an

attempt to introduce the knowledge of Hindu literature into the European world,

by forcing or corrupting the religious consciences of the Pundits, or professors

of their sacred doctrines. This reflexion was produced by the publication of Mr.

Halbed's translation of the Poottee, or code

of

[ 15 ]

of Hindoo laws; and is totally devoid of foundation. For myself I can declare

truly, that if the acquisition could not have been obtained but by such means as

have been supposed, I shouId never have fought it. It was contributed both

cheerfully and gratuitously, by men of the most respectable characters for

sanctity and learning in Bengal, who refused to accept more than the moderate

daily subsistence of one rupee each, during the term that they were employed on

the compilation; nor will it much redound to my credit, when I add, that they

have yet received no other reward for their meritorious labors. Very natural

causes may be ascribed for their reluctance to communicate the mysteries of

their learning to strangers, as those to whom they have been for some centuries

in subjection, never enquired into them, but to turn their religion into

derision, or deduce from them arguments to support the intolerant principles of

their own. From our nation they have received a different treatment, and are no

less eager to impart their knowledge than we are to receive it. I could say much

more in proof of this fact, but that it might look too much like self

commendation.

I have the honor to be, with respect,

SIR,

Your most obedient, and Most humble Servant,

WARREN HASTINGS.

Calcutta, 3d Dec, 1784

P. S. Since the above was written, Mr. Wilkins has transmitted to me a corrected

copy of his Translation, with the Preface and Notes much enlarged and improved.

In the former I meet with some complimentary

[ 16 ]

complimentary passages, which are certainly improper for a work published at my

own solicitation. But he is at too great a defiance to allow of their being sent

back to him for correction, without losing the opportunity, which I am unwilling

to lose, of the present dispatch; nor could they be omitted; if I thought myself

at liberty to expunge them, without requiring confiderable alterations in the

context. They must therefore stand ; and I hope that this explanation will be

admitted as a valid excuse for me in passing them.

W. H.

THE B H A G V A T- G E E T A,

O R DIALOGUES O F Krishna and Arjun

[ 19 ]

TO THE HONORABLE

WA R REN H A S T I N G S, EsQ.

GOVERNOR GENERAL, &c. &c.

HONORABLE SIR,

UNCONSCIOUS of the liberal purpose for which you intended the Gītā, when, at

your request, I had the honor to present you with a copy of the manuscript, I

was the less felicitous about its imperfections, because I knew that your

extensive acquaintance

[ 2O ]

with the customs and religious tenets of the Hindus would elucidate every

passage that was obscure, and I had so often experienced approbation from your

partiality, and correction from your pen : It was the theme of a pupil to his

preceptor .and patron. But since I received your commands to prepare it for the

public view, I feel all that anxiety which must be inseparable from one who, for

the first time, is about to appear before that awful tribunal ; and I should

dread the event, were I not convinced that the liberal sentiments expressed in

the letter you have done me honor to write, in recommendation of the work, to

the Chairman of the Direction, if permitted to accompany

[ 21 ]

it to the presss, would screen me, under its own intrinsic merit, from all

censure. The world, Sir, is so well acquainted with your boundless patronage in

gen eral, and of the personal encouragement you have constantly given to my

fellow-servants in _particular, to render themselves more capable of performing

their duty in the ..various branches of commerce, revenue, and policy, by the

study of the languages; with the laws and customs of the natives, that it must

deem the . first fruit of every genius you have raised a tribute justly due to

the source from which it sprang. As that personal encouragement alone first

excited emulation in my breast; and urged me to prosecute my particular studies,

[ 22 ]

even beyond the line of pecuniary reward, I humbly request you will permit me,

in token of my gratitude, to lay the Gītā

publicly at your fee_t.I have the honor to.fubfcrjbe myfelf, with great refpea,

Honorable Sir,

Your most obedient, and Most humble Servant,

Banaras,

19th November, 1734.

CHA WILKINS.

[ 23 ]

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE.

HE following work, forming part of the Mahabharat, an ancient Hindu poem, is a

dialogue supposed to have passed between Krishna, an incarnation of the Deity,

and his pupil and favorite Arjuna, one of the five sons of Pāndu, who is said to

have reigned about five thousand years ago, just before the commencement of a

famous battle fought on the plains of Kurushetra, near Delhi, at the beginning

of the Kaliyuga, or fourth and present age of the world, for the empire of

Bhārat-varsha, which, at that time, included all the countries that, in the

present division of the globe, are called India, extending from the borders of

Persia to the extremity of China; and from the snowy mountains to the southern

promontory.

The Brahmans esteem this work to contain all the grand mysteries of their

religion; and so careful are they to conceal it from the knowledge of those of a

different persuasion, and even the vulgar of their own, that the Translator

might have fought in vain for assistance, had not the liberal treatment they

have of late years ex perienced from the mildness of our government, the

tolerating principle's of our faith, and, above all, the personal attention paid

to the learned men of their order by him under whom auspicious administration

they have so long enjoyed,· in the midst of surrounding

[ 24 ]

troubles, the blessings of internal peace, and his exemplary encouragement, at

length happily created in their breasts a confidence in his countrymen

sufficient to remove almost every jealous prejudice from their minds.

It seems as if the principal design of these dialogues was to unite all the

prevailing modes of worship of those days; and, by setting up the doctrine of

the unity of the Godhead, in opposition to idolatrous sacrifices, and the

worship of images, to undermine the tenets inculcated by the Vedas; for although

the author dared not make a direct attack, either upon the prevailing prejudices

of the people, or the divine authority of those ancient books ; yet, by offering

eternal happiness to such as worship Brahman, the Almighty, whilst he declares

the reward of such as follow other Gods shall be but a temporary enjoyment of an

inferior heaven, for a period measured by the extent of their virtues, his

design was to bring about the downfall of Polytheism; or, at least, to induce

men to believe God present in every image before which they bent., and the

object of all their ceremonies and sacrifices.

The most learned Brahmans of the present times are Unitarians according to the

doctrines of Krishna; but, at the same time that they believe but in one God, an

universal spirit., they so far comply with the prejudices of the vulgar, as

outwardly to perform all the ceremonies inculcated by the Vedas, such as

sacrifices, ablutions, &c. They do this, probably, more for the support of their

own consequence, which could only arise from the great ignorance of the people,

than in compliance with the dictates of Krishna: indeed, this ignorance, and

these ceremonies, are as much the bread of the Brahmans, as the superstition of

the vulgar is the support of the priesthood in many other countries.

The reader will have the liberality to excuse the obscurity of many passages,

and the confusion of sentiments which runs through the whole in its present

form. It was the Transistor’s business to remove as much of this obscurity and

confusion as his knowledge

[ 25 ]

and abilities would permit. This he hath attempted in his Notes ; but as he is

conscious they are still insufficient to remove the veil of mystery, he begs

leave to remark, in his own justification·, that the text is but imperfectly

understood by the most learned Brahmans of the present times; and that, small as

the work may appear, it has had more comments than the Revelations. These have

not been totally disregarded; but, as they were frequently found more obscure

than the original they were intended to elucidate, it was thought better to

leave many of the most difficult passages for the exercise of the reader's own

judgment, than to mislead him by such wild opinions as no one syllable of the

text could authorize.

Some apology is also due for a few original words and proper names that are left

untranslated, and unexplained. The Translator was frequently too diffident of

his own abilities to hazard a term that did but nearly approach the sense of the

original, and too ignorant, at present, of the mythology of this ancient people,

to venture any very particular account, in his Notes, of such Deities, Saints,

and Heroes, whose names are but barely mentioned in the text. But 1hould the

fame Genius, whose approbation first kindled emulation in his breast, and who

alone hath urged him to undertake, and sup ported him through the execution of

far more laborious tasks than this, find no cause to withdraw his countenance,

the Translator may be encouraged to prosecute the study of the theology and

mythology of the Hindus, for the future entertainment of the curious.

It is worthy to be noted, that Krishna throughout the whole, mentions only three

of the four books of the Vedas, the most ancient scriptures of the Hindus, and

those the three first, according to the present order. This is a very curious

circumstance, as it is the present belief that the whole four were promulgated

by Brahma at the creation. The proof then of there having been but three before

his time, is more than presumptive, and that so many actually existed before his

appearance; and as the fourth mentions the name of Krishna, it is equally proved

that it is a posterior work.

[ 26 ]

This observation has escaped all the commentators. and was received with great

astonishment by the Pandit1 who was consulted in the translation.

The Transistor has not as yet had leisure to read any part of the ancient

scriptures. He is told, that a very few of the original num ber of chapters are

now to be found, and that the study of these is so difficult, that there are but

few men in Banaras who understand any part of them. If We may believe the

Mahahharat, they were almost lost five thousand years ago ; when Vyasa, so named

from having superintended the compilation of them, collected the scattered

leaves, and, by the assistance of his disciples, collated and preserved them in

four books.

As a regular mode hath been followed in the orthography of the proper names, and

other original words, the reader may be guided in the pronunciation of them by

the following explanation.

(g) has always the hard found of that letter in gun.

(j) the soft found of (g), or of (J) in James.·

(y) is generally to be considered as a consonant, and to be pronounced as that

letter before a vowel, in the word yarn.

(h) preceded by another consonant, denotes it to be aspirated.

(a) is always to be pronounced short, like (u) in Butter.

(ā) long, and broad, like (a) in all, call.

(ee) short, as (i) in it.

(ēē) long.

(oo) short, as (oo) in faot.

(ōō) long.

(ē) open and long.

(ī) as that letter is pronounced in our alphabet.

(ō) long, like (6) in over.

(ow) long, like (ow) in how.

[ 27 ]

THE BHAGAVAD-GITA

OR DIALOGUES OF KRISHNA AND ARJUN

LECTURE 1 . Chapter 1

THE BRIEF OF ARJUNA

Dḥṛtarāṣṭra

said,

“TELL me, O Sanjay, what the people of my own party, and those of the Pāṇḍu, who

are assembled at Kuru-ṣetra resolved for war, have been doing

[ 28 ]

SAṀJAYA v replied,

"Duryodhana having seen the army of the Pāṇḍus Drawn up for battle, went to his

Preceptor, and addressed him in the following words:''

" Behold O master, said he, the mighty army of the sons of Pāṇḍu drawn forth by

thy pupil, the experienced son of Drupada. In it are heroes, such as Bhīma or

Arjuna : there is Yuyudhāna, and Vīrāṭa, and Drūpada, and Dhṛṣṭaketu, and

Chekītana, and the valiant prince of Kāśi, and Purujit, and Kuntibhoja, and

Śaibya a mighty chief, and Yudhāmanyu-Pīkranta,. and the daring Uttamauja; so

the son of Subhadrā, and the sons of Krishnā the daughter of Drūpada, all of

them great in arms. Be acquainted also with the names of those of our party who

are the most distinguished. I will mention a few of those who are among my

generals, by way of example. There is thyself, my Preceptor, and Bhīṣma, and

Kṛpa the conqueror in battle, and As vatthāma, and Vikarṇa, and the son of

Somadatta,8.

with others in vast numbers who for my service have forsaken the love of life.

They are all of them practiced in the use of arms, and experienced in every mode

of fight. Our innumerable forces are commanded by Bhīṣma,. and the

inconsiderable army of our foes is led by Bhīma.1O

[ 29 )

Let all the generals, according to their respective divisions,. stand in their

posts, and one and all resolve Bhīṣma to support."

The ancient chief 1 , and brother of the grandsire of the Kurus, then,

shouting with a voice like a roaring lion, blew his shell to raise the spirits

of the Kuru. chief; and instantly innumerable shells, and other warlike instru

ments, were struck up on all sides, so that the clangor · was excessive. At this

time Krishna and Arjun were standing in a splendid chariot drawn by white

horses. They also sounded their shells, which were of celestial form: the name

of the one which was blown by Krishna, was Panchajanya, and that of Arjuna was

called Deva-datta. Bhīma, of dreadful deeds, blew his ca pacious shell Pouṇḍra,

and Yudhiṣṭhira, the royal son of Kuntee, sounded Anantavijaya. Nakula and

Sahadeva blew their shells : Sughoṣa and Maṇipuṣpaka.16 The prince of Kāśi of

the mighty bow, Śikhaṇḍin, Dhṛṣṭadyumna, Virāṭa, Sātyaki of invincible arm

Drupada and the sons of his royal daughter Krishna, with the son of Subhadrā,

and all the other chiefs and nobles, blew also their respective shells; so that

their shrill sounding voices pierced the hearts.

[ 3O ]

of the Kurus, and re-echoed with a dreadful noise from heaven to earth. In the

meantime Arjuna, perceiving that the sons of Dḥṛtarāṣṭra ready to begin the

fight, and that the weapons began to fly abroad, having taken up his bow,

addressed Krishna in the following words:

ARJUN

I pray thee, Krishna, cause my chariot to be driven and placed between the two

armies, that I may behold who are the men that stand ready, anxious to commence

the bloody fight; and with whom it is that I am to fight in this ready field;

and who they are that are here assembled to support the vindictive son of

Dḥṛtarāṣṭra in the battle."

Krishna being thus addressed by Arjuna, drove the chariot; and, having caused it

to halt in the midst of the space in front of the two armies, Arjuna cast his

eyes towards the ranks of the Kurus, and behold where stood the aged Bhīṣma, and

Drona, with all the chief° nobles of their party. He looked at both the armies,

and beheld, on either side, none but grandsires, uncles, cousins, tutors, sons,

and brothers, near relations, or bosom friends; and, when he had gazed for a

while, and beheld such friends

[ 31 ]

as these prepared for the fight, he was seizcd with extreme pity and

compunction, and uttered his sorrow in the following words :

Arjuna

" Having beheld, O Krishna my kindred thus standing anxious for the fight, my

members fail me, my coun tenance withereth, the hair standeth an end upon my

body, and all my frame trembleth with horror. Even Gāṇḍiva my bow escapeth from

my hand, and my skin is parched and dried up. I am not able to stand; for my

understanding, as it were, turneth round, and I behold inauspicious omens on all

sides. When I shall have destroyed my kindred, shall I longer look for

happiness? I. wish not for victory, Krishna; I want not dominion ; I want not

pleasure; for what is dominion, and the enjoy ments of life, or even life

itself, when those, for whom dominion, pleasure, and enjoyment were to be

coveted. have abandoned life and fortune and stand here in the field ready for

the battle ? Tutors, sons and fathers, grandsires and grandsons, uncles and

nephews, cousins. kindred, and friends I Although they would kill me, I will not

to fight them; no not even for the dominion of the three regions of the

universe, much less for this little earthI Having killed the sons of

Dhṛitarāshṭra, what

[ 32 ]

pleasure, O Krishna, can we enjoy ? Should we destroy them, tyrants as they are,

sin would take refuge with us. It therefore behoveth us not to kill such near

relations as these. How, O Krishna, can we be happy hereafter, when we have been

the murderers of our race? What if they, whose minds are depraved by the lust of

power, feel no sin in the extirpation of their race, no crime in the murder of

their friends, is that a reason why we should not resolve to turn away from such

a crime, we who abhor the sin of extirpating the kindred of our blood ? In the

destruction of a family, the ancient virtue of the family is lost. Upon the loss

of virtue, vice and impiety overwhelm the whole of a race. From the influence of

impiety the females of a family grow vicious; and from women that are become

vicious are born the spurious brood called Varṇasaṁkara. The saṁkara provideth

Hell 5 both for those which are slain and those which survive; and their

forefathers 6 being deprived of the ceremonies of cakes and water offered to

their manes, sink into the infernal regions. By the crimes of those who murder

their own relations, fore cause of contamination and birth of Varṇasaṁkara, the

family virtue, and the virtue of a whole tribe is for ever done away; and we

have been told, O Krishna, that the habitation of those

[ 33 ]

mortals whose generation hath lost its virtue, shall be in Hell. Woe is me I

what a great crime are we prepared to commit I ·Alas! that for the lust of the

enjoyments of dominion we stand here ready to murder the kindred of our own

blood I I would rather patiently suffer that the sons of Dhṛitarāshṭra, .with

their weapons in their hands, should come upon me, and, unopposed, kill me

unguarded in the field."

When Arhuna had ceased to speak, he sat down in the chariot between the two

armies; and having put away his bow and arrows, his heart was overwhelmed with

affliction,